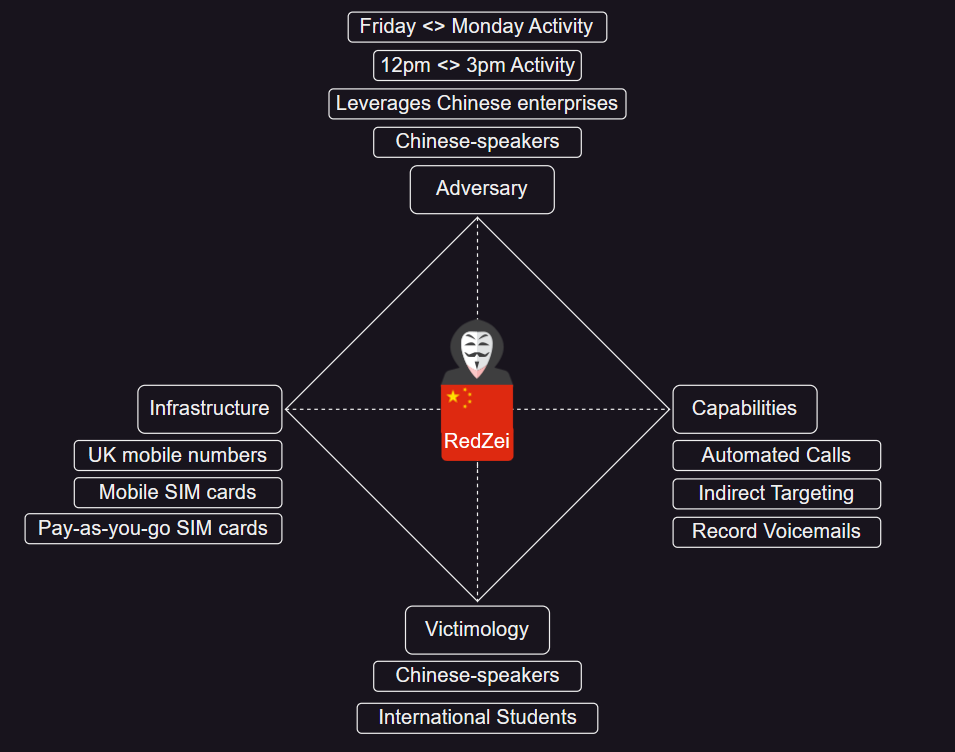

Tracking Adversaries: RedZei, Chinese-speaking scammers targeting Chinese students in the UK

Welcome to the final BushidoToken blog of 2022. Over the last year or so, an associate of mine in the UK has been targeted by a persistent Chinese-speaking scammer. The scammer often calls once or twice a month from a unique UK-based phone number and, if left unanswered, leaves an unusual automated voicemail.

I got the recorded voicemails and identified that they are almost certainly scam calls from Chinese-speaking fraudsters targeting Chinese international students at universities in the UK. I have tracked this campaign for over a year and built a profile on the group's activities based on just the calls and voicemails they have left. I am now disclosing these attempts and subsequently tracking this activity group as "RedZei" (aka "RedThief").

The RedZei fraudsters have chosen their targets carefully, researched them and realized it was a rich victim group that is ripe for exploitation. A quick OSINT search found several recent articles about this apparently lucrative malicious campaign:

- https://www.itv.com/news/utv/2022-05-09/students-scammed-out-of-105k-after-bogus-chinese-authorities-calls

- https://www.bournemouth.ac.uk/news/2022-12-15/scam-warning-chinese-students

- https://news.liverpool.ac.uk/2021/09/29/fraud-scam-warning-for-international-students/

- https://www.ucl.ac.uk/students/news/2022/jun/fake-police-scam-targeting-chinese-students

- https://www.theguardian.com/money/2019/aug/31/fraudsters-target-chinese-students-in--visa-scam

The compelling aspect about this scam is how well the attempts were crafted and the careful tradecraft employed to evade traditional steps users take to block such scams. For each wave of scam calls, RedZei will mostly use a new pay-as-you-go +44 UK phone number every time from one of the main mobile network operators (MNOs). This essentially renders blocking the scammers phone numbers ineffective.

Further, as RedZei alternates between SIMs from several UK mobile carriers it is difficult for the telecom companies to stop this type of activity. As the activity is also in Chinese, the carriers are less likely to investigate this campaign to additional effort required. The RedZei group, and others like it, are therefore effectively operating with impunity and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

Figure 1 contains a timeline of when these scam calls are made, including the origin of the caller's number, the mobile carrier (identified using OSINT), the date and time of the call, as well as the theme of the call. As I am not a Chinese speaker and did not get all of the voicemails verified by Chinese speakers, the theme of some of them is currently unknown. The phone numbers in plaintext are available in a Gist here.